In general, gamma spectroscopy is the study of the energy spectra of gamma ray sources, such as in the nuclear industry, geochemical investigation, and astrophysics. Spectroscopes, or spectrometers, are sophisticated devices designed to measure the spectral power distribution of a source. The incident radiation generates a signal that allows to determine the energy of the incident particle.

Most radioactive sources produce gamma rays, which are of various energies and intensities. Gamma rays frequently accompany the emission of alpha and beta radiation. When these emissions are detected and analyzed with a spectroscopy system, a gamma-ray energy spectrum can be produced. Gamma rays from radioactive decay are in the energy range from a few keV to ~8 MeV, corresponding to the typical energy levels in nuclei with reasonably long lifetimes. As was written, they are produced by the decay of nuclei as they transition from a high energy state to a lower state. A detailed analysis of this spectrum is typically used to determine the identity and quantity of gamma emitters present in a sample, and is a vital tool in radiometric assay. The gamma spectrum is characteristic of the gamma-emitting nuclides contained in the source.

Gamma Ray Spectrometer – Gamma Ray Spectroscope

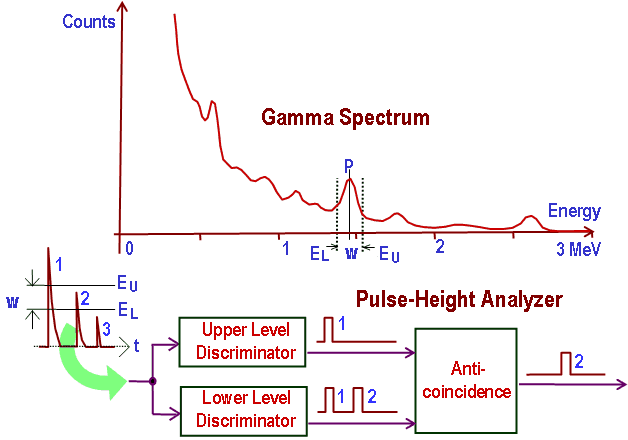

The gamma spectroscope consists of a suitable scintillator crystal, a photomultiplier tube, and a circuit for measuring the height of the pulses produced by the photomultiplier. The advantages of a scintillation counter are its efficiency and the high precision and counting rates that are possible. These latter attributes are a consequence of the extremely short duration of the light flashes, from about 10-9 (organic scintillators) to 10-6 (inorganic scintillators) seconds. The intensity of the flashes and the amplitude of the output voltage pulse are proportional to the energy of the radiation. The pulses are counted and sorted by their height, producing a x-y plot of scintillator flash brightness vs number of the flashes, which approximates the energy spectrum of the incident radiation, with some additional artifacts. A monoenergetic gamma ray produces a photopeak at its energy. The scintillation detector also shows response at the lower energies, caused by Compton scattering, two smaller escape peaks at energies 0.511 and 1.022 MeV below the photopeak for the creation of electron-positron pairs when one or both annihilation photons escape, and a backscatter peak. Higher energies can be measured when two or more photons strike the detector almost simultaneously, appearing as sum peaks with energies up to the value of two or more photopeaks added.

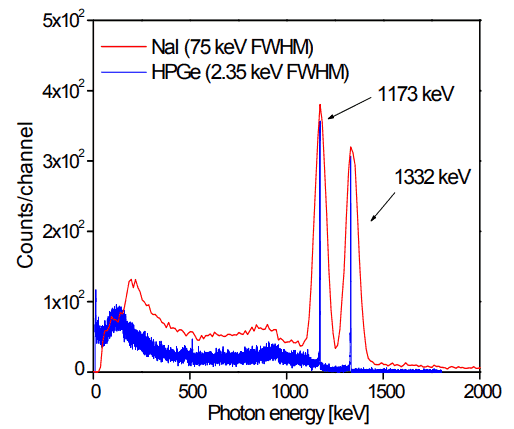

The scintillation based spectrometers have the advantage of availability in large size and high density which can result in high interaction probabilities for gamma rays. On the other hand, their energy resolution scintillators is poor, when compared to high purity germanium detectors. Germanium detectors are better choice for separation of closely spaced gamma energies. The typical energy resolution of a good germanium system is few tenths of a percent compared to 5-10 % for sodium iodide.

Gamma Spectrum Structure – The Cobalt-60 Spectrum

Analysis of gamma spectra is very interesting, since it has a structure and workers must distinguish between true pulses to be analyzed and accompanying pulses from different sources of radiation. We will show the structure of the gamma spectrum on the example of cobalt-60 measured by NaI(Tl) scintillation detector and by the HPGe detector. The HPGe detector allows the separation of many closely spaced gamma lines, which is very beneficial for measuring multi-gamma emitting radioactive sources.

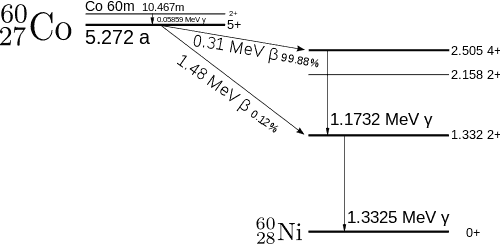

Cobalt-60 is an artificial radioactive isotope of cobalt with a half-life of 5.2747 years. It is synthetically produced by neutron activation of cobalt-59 in nuclear reactors. Cobalt-60 is a common calibration source found in many laboratories. The gamma spectrum has two significant peaks, one at 1173.2 keV and another at 1332.5 keV. Good scintillation detectors should have adequate resolution to separate the two peaks. For HPGe detectors, these peaks are perfectly separated.

As can be seen from the figure, there are two gamma ray photopeaks. Both detectors also show response at the lower energies, caused by Compton scattering, two smaller escape peaks at energies 0.511 and 1.022 MeV below the photopeak for the creation of electron-positron pairs when one or both annihilation photons escape, and a backscatter peak. Higher energies can be measured when two or more photons strike the detector almost simultaneously, appearing as sum peaks with energies up to the value of two or more photopeaks added.

General structure of gamma rays spectrum usually has the following principle features:

- Photopeaks are full energy peaks, that are created, when γ-ray transfers its full energy (hω −Ebinding) into the sensitive material (scintillation crystal or germanium crystal). Than a single delta function should be observed in the spectrum.The cobalt-60 spectrum contains two photopeaks, one at 1173.2 keV and another at 1332.5 keV.

- Compton Continuum. In the crystal, a gamma ray undergoes a number of interactions, but for intermediate energies compton scattering dominates. In compton scattering, the incident gamma ray photon is deflected through an angle Θ with respect to its original direction. The photon transfers a portion of its energy to the recoil electron. The energy transferred to the recoil electron can vary from zero to a large fraction (maximum E) of the incident gamma ray energy, because all angles of scattering are possible. The size of the scintillation crystal changes the ratio between photopeak and Compton continuum. For an infinitely large spherical detector centered around a source no photons would be able to escape and only a photopeak would be seen on the spectrum. For very small detectors the chance for a photon to leave after Compton scattering is high and the Compton continuum would be large compared to the photopeak.

- Compton Edge. The Compton edge is a feature of the spectrograph that results from the Compton scattering in the scintillator or detector. This feature is due to photons that undergo Compton scattering with a scattering angle of 180° and then escape the detector. When a gamma ray scatters off the detector and escapes, only a fraction of its initial energy can be deposited in the sensitive layer of the detector. It depends on the scattering angle of the photon, how much energy will be deposited in the detector. This leads to a spectrum of energies. The Compton edge energy corresponds to full backscattered photon. The counts between Compton edge and the photopeaks are caused by multiple Compton scattering events, where scattered gamma photon exits the sensitive material.

Sometimes the structure of gamma rays spectrum has the following secondary features:

-

Compton edge of 60Co on gamma spectrometer Na(Tl). Backscatter Peak. A Compton backscatter peak is found when γ-rays enter the material around the detector and are scattered back into the detector. Gamma photon can interact by Compton mechanism in shield or surrounding materials and is backscattered out of a material into sensitive volume. Maximum photon energy in this interaction is ~200 keV regardless of initial photon energy. This results in a secondary peak at -200 keV.

- X-ray Peaks. When the gamma rays undergoes photoelectric effect in surrounding materials (for example lead shield) the outgoing X-ray can be captured again by the detector. This gives an characteristic X-ray peak with an energy depending on the material it came from. In case of lead the characteristic X-ray energies is in the 72-84 keV range. Photoelectric absorption by K-shell electron in lead of shielding, resulting in a K-shell vacancy. The K -> L transition for lead = 72 keV. If this characteristic x-ray is absorbed in the crystal then a secondary peak at 72 keV is observed.

- Coincidence Peak. Simultaneous absorption of two gamma photons in crystal, resulting in a peak higher in energy than the photopeak. The gamma photons may result from serial isomeric transitions (e.g. 2 keV plus 1332.5 keV in case of cobalt-60) or simultaneous decays in separate radionuclides (e.g. 2 x 1173.2 keV in case of cobalt-60).

- Annihilation Peak. For high energy gamma rays (greater than 1.02 MeV), electron-positron pair production is a possible interaction. But a positron may then annihilate in the detector or in the surrounding material. If both 0.51 MeV annihilation photons are absorbed in the crystal, a secondary peak 1.02 MeV below the photopeak can be found. If one annihilation photon is absorbed and the second exits the crystal, then 0.51 MeV is removed from the photopeak, resulting in a secondary peak 0.51 MeV below the photopeak. The probability is greater that one annihilation photon will be absorbed.

We hope, this article, Spectroscopy using Scintillation Counter, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about radiation and dosimeters.