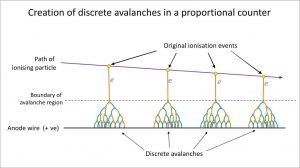

A proportional counter, also known as the proportional detector, is an electrical device that detects various types of ionizing radiation. The voltage of detector is adjusted so that the conditions correspond to the proportional region. In this region, the voltage is high enough to provide the primary electrons with sufficient acceleration and energy so that they can ionize additional atoms of the medium. These secondary ions (gas amplification) formed are also accelerated causing an effect known as Townsend avalanches, which creates a single large electrical pulse.

Advantages of Proportional Counters

- Amplification. Gaseous proportional counters usually operate in high electric fields of the order of 10 kV/cm and achieve typical amplification factors of about 105. Since the amplification factor is strongly dependent on the applied voltage, the charge collected (output signal) is also dependent on the applied voltage and proportional counters require constant voltage. The high amplification factor of the proportional counter is the major advantage over the ionization chamber.

- Sensitivity. The process of charge amplification greatly improves the signal-to-noise ratio of the detector and reduces the subsequent electronic amplification required. Since the process of charge amplification greatly improves the signal-to-noise ratio of the detector, the subsequent electronic amplification is usually not required. Proportional counter detection instruments are very sensitive to low levels of radiation. Moreover, when measuring current output, a proportional detector is useful for dose rates

since the output signal is proportional to the energy deposited by ionization and

therefore proportional to the dose rate. -

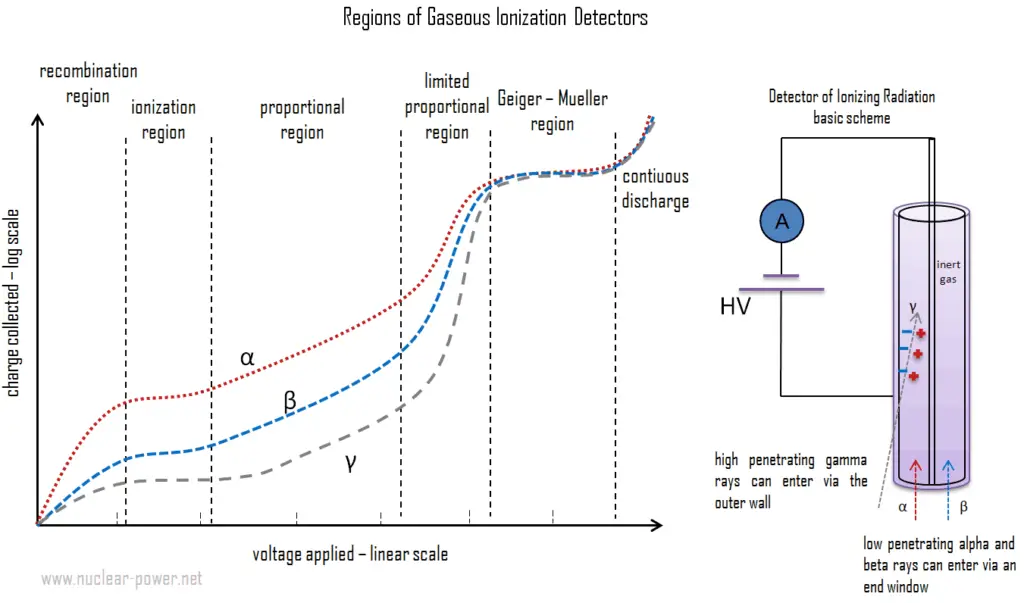

This diagram shows the number of ion pairs generated in the gas-filled detector, which varies according to the applied voltage for constant incident radiation. The voltages can vary widely depending upon the detector geometry and the gas type and pressure. This figure schematically indicates the different voltage regions for alpha, beta and gamma rays. There are six main practical operating regions, where three (ionization, proportional and Geiger-Mueller region) are useful to detect ionizing radiation. Alpha particles are more ionising than beta particles and than gamma rays, so more current is produced in the ion chamber region by alpha than beta and gamma, but the particles cannot be differentiated. More current is produced in the proportional counting region by alpha particles than beta, but by the nature of proportional counting it is possible to differentiate alpha, beta and gamma pulses. In the Geiger region, there is no differentiation of alpha and beta as any single ionisation event in the gas results in the same current output. Spectroscopy. By proper functional arrangements, modifications, and biasing, the proportional counter can be used to detect alpha, beta, gamma, or neutron radiation in mixed radiation fields. Moreover, proportional counters are capable of particle identification and energy measurement (spectroscopy). The pulse height reflects the energy deposited by the incident radiation in the detector gas. As such, it is possible to distinguish the larger pulses produced by alpha particles from the smaller pulses produced by beta particles or gamma rays.

Disadvantages of Proportional Counters

- Constant Voltage. When instruments are operated in the proportional region, the voltage must be kept constant. If a voltage remains constant the gas amplification factor also does not change. The main drawback to using proportional counters in portable instruments is that they require a very stable power supply and amplifier to ensure constant operating conditions (in the middle of the proportional region). This is difficult to provide in a portable instrument, and that is why proportional counters tend to be used more in fixed or lab instruments.

- Quenching. For each electron collected in the chamber, there is a positively charged gas ion left over. These gas ions are heavy compared to an electron and move much more slowly. Free electrons are much lighter than the positive ions, thus, they are drawn toward the positive central electrode much faster than the positive ions are drawn to the chamber wall. The resulting cloud of positive ions near the electrode leads to distortions in gas multiplication. Eventually the positive ions move away from the positively charged central wire to the negatively charged wall and are neutralized by gaining an electron. In the process, some energy is given off, which causes additional ionization of the gas atoms. The electrons produced by this ionization move toward the central wire and are multiplied en route. This pulse of charge is unrelated to the radiation to be detected and can set off a series of pulses. In practice the termination of the avalanche is improved by the use of “quenching” techniques.

Special Reference: U.S. Department of Energy, Instrumantation and Control. DOE Fundamentals Handbook, Volume 2 of 2. June 1992.

We hope, this article, Advantage and Disadvantage of Proportional Counters, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about radiation and dosimeters.