In radiation protection, the sievert is a derived unit of equivalent dose and effective dose. The sievert represents the equivalent biological effect of the deposit of a joule of gamma rays energy in a kilogram of human tissue. But what is the relationship between becquerels (radioactivity) and sieverts (equivalent dose)?

In radiation protection, the sievert is a derived unit of equivalent dose and effective dose. The sievert represents the equivalent biological effect of the deposit of a joule of gamma rays energy in a kilogram of human tissue. But what is the relationship between becquerels (radioactivity) and sieverts (equivalent dose)?

In previous chapters, we have discussed radioactivity and the intensity of a radioactive source, measured usually in becquerels. But any radioactive source represents no biological risk as long as it is isolated from the environments. However, when people or another system (also non-biological) are exposed to radiation, energy is deposited in the material and radiation dose is delivered.

It is therefore very important to distinguish between radioactivity of a radioactive source and the radiation dose which may result from the source. Generally, the radiation dose depends on the following factors regarding to the radioactive source:

- Activity. Activity of the source directly influences the radiation dose deposited in the material.

- Type of radiation. Each type of radiation interacts with matter in a different way. For example charged particles with high energies can directly ionize atoms. On the other hand electrically neutral particles interacts only indirectly, but can also transfer some or all of their energies to the matter.

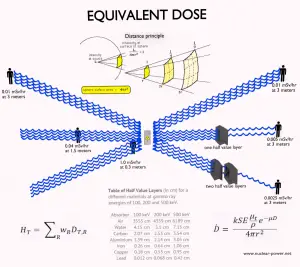

- Distance. The amount of radiation exposure depends on the distance from the source of radiation. Similarly to a heat from a fire, if you are too close, the intensity of heat radiation is high and you can get burned. If you are at the right distance, you can withstand there without any problems and moreover it is comfortable. If you are too far from heat source, the insufficiency of heat can also hurt you. This analogy, in a certain sense, can be applied to radiation also from radiation sources.

- Time. The amount of radiation exposure depends directly (linearly) on the time people spend near the source of radiation.

- Shielding. Finally, the radiation dose also depends on the material between the source and the object. If the source is too intensive and time or distance do not provide sufficient radiation protection, the shielding can be used.

The danger of ionizing radiation lies in the fact that the radiation is invisible and not directly detectable by human senses. People can neither see nor feel radiation, yet it deposits energy to the molecules of the body. The energy is transferred in small quantities for each interaction between the radiation and a molecule and there are usually many such interactions.

Sievert and Gray

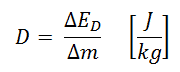

Absorbed dose is defined as the amount of energy deposited by ionizing radiation in a substance. Absorbed dose is given the symbol D. The absorbed dose is usually measured in a unit called the gray (Gy), which is derived from the SI system. The non-SI unit rad is sometimes also used, predominantly in the USA.

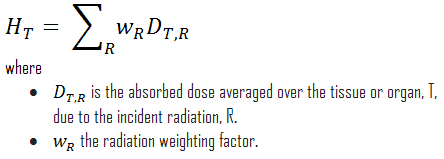

For radiation protection purposes, the absorbed dose is averaged over an organ or tissue, T, and this absorbed dose average is weighted for the radiation quality in terms of the radiation weighting factor, wR, for the type and energy of radiation incident on the body. The radiation weighting factor is a dimensionless factor used to determine the equivalent dose from the absorbed dose averaged over a tissue or organ and is based on the type of radiation absorbed. The resulting weighted dose was designated as the organ- or tissue equivalent dose:

An equivalent dose of one Sievert represents that quantity of radiation dose that is equivalent, in terms of specified biological damage, to one gray of X-rays or gamma rays. A dose of one Sv caused by gamma radiation is equivalent to an energy deposition of one joule in a kilogram of a tissue. That means one sievert is equivalent to one gray of gamma rays deposited in certain tissue. On the other hand, similar biological damage (one sievert) can be caused only by 1/20 gray of alpha radiation (due to high wR of alpha radiation). Therefore, the sievert is not a physical dose unit. For example, an absorbed dose of 1 Gy by alpha particles will lead to an equivalent dose of 20 Sv. This may seem to be a paradox. It implies that the energy of the incident radiation field in joules has increased by a factor of 20, thereby violating the laws of Conservation of energy. However, this is not the case. Sievert is derived from the physical quantity absorbed dose, but also takes into account the biological effectiveness of the radiation, which is dependent on the radiation type and energy. The radiation weighting factor causes that the sievert cannot be a physical unit.

One sievert is a large amount of equivalent dose. A person who has absorbed a whole body dose of 1 Sv has absorbed one joule of energy in each kg of body tissue (in case of gamma rays).

Equivalent doses measured in industry and medicine often have usually lower doses than one sievert, and the following multiples are often used:

1 mSv (millisievert) = 1E-3 Sv

1 µSv (microsievert) = 1E-6 Sv

Conversions from the SI units to other units are as follows:

- 1 Sv = 100 rem

- 1 mSv = 100 mrem

Radiation Weighting Factors – ICRP

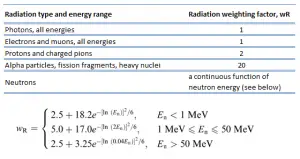

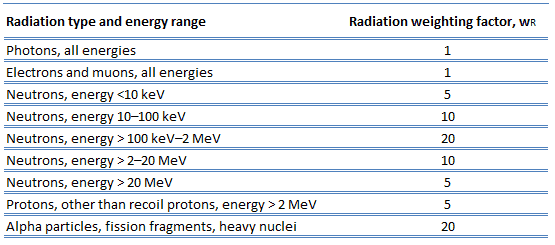

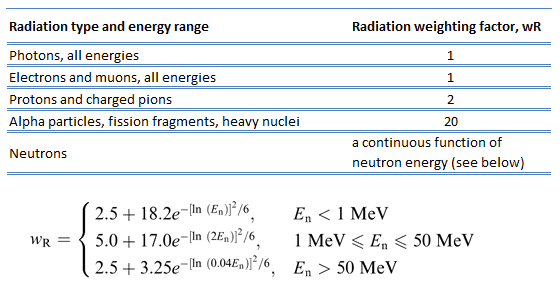

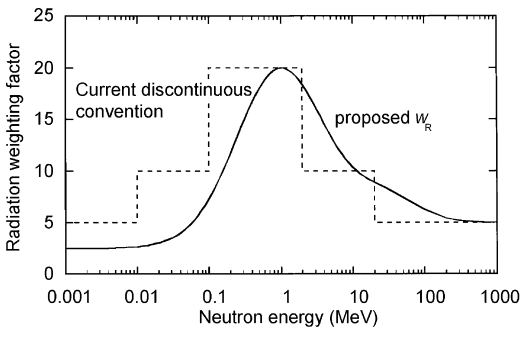

For photon and electron radiation, the radiation weighting factor has the value 1 independently of the energy of the radiation and for alpha radiation the value 20. For neutron radiation, the value is energy-dependent and amounts to 5 to 20.

In 2007 ICRP published a new set of radiation weighting factors (ICRP Publ. 103: The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection). These factors are given below.

As shown in the table, a wR of 1 is for all low-LET radiations, i.e. X-rays and gamma rays of all energies as well as electrons and muons. A smooth curve, considered an approximation, was fitted to the wR values as a function of incident neutron energy. Note that En is the neutron energy in MeV.

Thus for example, an absorbed dose of 1 Gy by alpha particles will lead to an equivalent dose of 20 Sv, and an equivalent dose of radiation is estimated to have the same biological effect as an equal amount of absorbed dose of gamma rays, which is given a weighting factor of 1.

See also: Quality Factor

Effective Dose – Sieverts

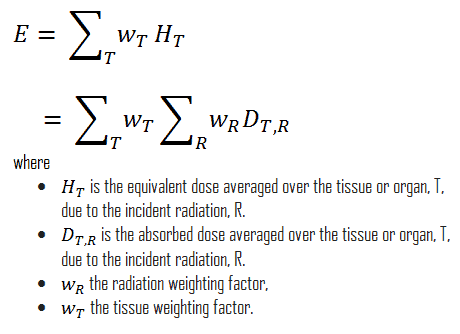

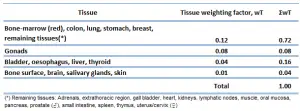

The effective dose is a dose quantity defined as the sum of the tissue-equivalent doses weighted by the ICRP organ (tissue) weighting factors, wT, which takes into account the varying sensitivity of different organs and tissues to radiation.

The effective dose is a dose quantity defined as the sum of the tissue-equivalent doses weighted by the ICRP organ (tissue) weighting factors, wT, which takes into account the varying sensitivity of different organs and tissues to radiation.

Effective dose allows to determine the biological consequences of partial irradiation (non-uniform) to consequences of complete irradiation. Various body tissues react to ionising radiation in different ways, so the ICRP has assigned sensitivity factors to specified tissues and organs so that the effect of partial irradiation can be calculated if the irradiated regions are known.

In Publication 60, the ICRP defined effective dose as the doubly weighted sum of absorbed dose in all the organs and tissues of the body. Dose limits are set in terms of effective dose and apply to the individual for radiological protection purposes, including the assessment of risk in general terms. Mathematically, the effective dose can be expressed as:

Examples of Doses in Sieverts

We must note that radiation is all around us. In, around, and above the world we live in. It is a natural energy force that surrounds us. It is a part of our natural world that has been here since the birth of our planet. In the following points we try to express enormous ranges of radiation exposure, which can be obtained from various sources.

- 0.05 µSv – Sleeping next to someone

- 0.09 µSv – Living within 30 miles of a nuclear power plant for a year

- 0.1 µSv – Eating one banana

- 0.3 µSv – Living within 50 miles of a coal power plant for a year

- 10 µSv – Average daily dose received from natural background

- 20 µSv – Chest X-ray

- 40 µSv – A 5-hour airplane flight

- 600 µSv – mammogram

- 1 000 µSv – Dose limit for individual members of the public, total effective dose per annum

- 3 650 µSv – Average yearly dose received from natural background

- 5 800 µSv – Chest CT scan

- 10 000 µSv – Average yearly dose received from natural background in Ramsar, Iran

- 20 000 µSv – single full-body CT scan

- 175 000 µSv – Annual dose from natural radiation on a monazite beach near Guarapari, Brazil.

- 5 000 000 µSv – Dose that kills a human with a 50% risk within 30 days (LD50/30), if the dose is received over a very short duration.

As can be seen, low-level doses are common for everyday life. The previous examples can help illustrate relative magnitudes. From biological consequences point of view, it is very important to distinguish between doses received over short and extended periods. An “acute dose” is one that occurs over a short and finite period of time, while a “chronic dose” is a dose that continues for an extended period of time so that it is better described by a dose rate. High doses tend to kill cells, while low doses tend to damage or change them. Low doses spread out over long periods of time don’t cause an immediate problem to any body organ. The effects of low doses of radiation occur at the level of the cell, and the results may not be observed for many years.

Calculation of Shielded Dose Rate in Sieverts

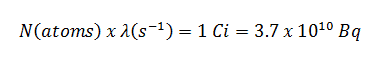

Assume the point isotropic source which contains 1.0 Ci of 137Cs, which has a half-life of 30.2 years. Note that the relationship between half-life and the amount of a radionuclide required to give an activity of one curie is shown below. This amount of material can be calculated using λ, which is the decay constant of certain nuclide:

About 94.6 percent decays by beta emission to a metastable nuclear isomer of barium: barium-137m. The main photon peak of Ba-137m is 662 keV. For this calculation, assume that all decays go through this channel.

Calculate the primary photon dose rate, in gray per hour (Gy.h-1), at the outer surface of a 5 cm thick lead shield. Then calculate the equivalent dose rate. Assume that this external radiation field penetrate uniformly through the whole body. Primary photon dose rate neglects all secondary particles. Assume that the effective distance of the source from the dose point is 10 cm. We shall also assume that the dose point is soft tissue and it can reasonably be simulated by water and we use the mass energy absorption coefficient for water.

See also: Gamma Ray Attenuation

See also: Shielding of Gamma Rays

Solution:

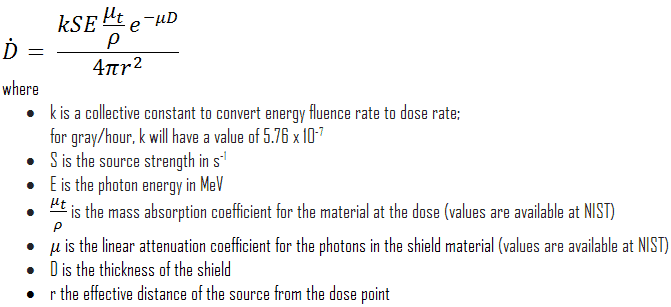

The primary photon dose rate is attenuated exponentially, and the dose rate from primary photons, taking account of the shield, is given by:

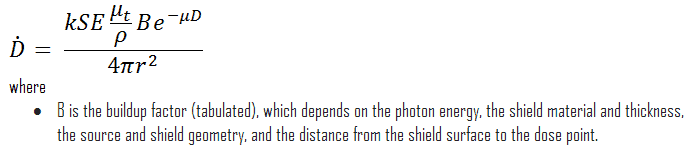

As can be seen, we do not account for the buildup of secondary radiation. If secondary particles are produced or if the primary radiation changes its energy or direction, then the effective attenuation will be much less. This assumption generally underestimates the true dose rate, especially for thick shields and when the dose point is close to the shield surface, but this assumption simplifies all calculations. For this case the true dose rate (with the buildup of secondary radiation) will be more than two times higher.

To calculate the absorbed dose rate, we have to use in the formula:

- k = 5.76 x 10-7

- S = 3.7 x 1010 s-1

- E = 0.662 MeV

- μt/ρ = 0.0326 cm2/g (values are available at NIST)

- μ = 1.289 cm-1 (values are available at NIST)

- D = 5 cm

- r = 10 cm

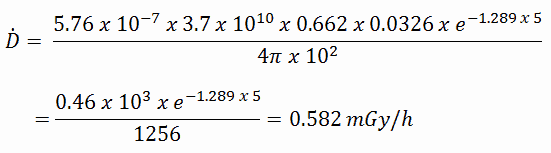

Result:

The resulting absorbed dose rate in grays per hour is then:

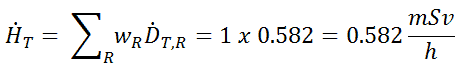

Since the radiation weighting factor for gamma rays is equal to one and we have assumed the uniform radiation field, we can directly calculate the equivalent dose rate from the absorbed dose rate as:

If we want to account for the buildup of secondary radiation, then we have to include the buildup factor. The extended formula for the dose rate is then:

——–

We hope, this article, Sievert – Gray – Becquerel – Conversion – Calculation, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about radiation and dosimeters.